All content copyright ©Can Sönmez

Click here for the comprehensive BJJ History Index]

CONTENTS

Introduction

- Origins

- Jigoro Kano and the Foundation of Judo

- The Gracie Family

- Carlson & Rolls

- BJJ Comes to America

- Royce and the UFC

- MMA: Growth & Change

- The Turning Point

- PRIDE & The Gracie Hunter

- BJJ in the UK

Footnotes

Sources

Introduction: I first started looking into the background of BJJ when I began watching DVDs of the early Ultimate Fighting Championship, several years before I began my training at the Roger Gracie Academy. When I find something I enjoy, I like to find out as much as possible about the subject, so start researching on the net, in books, DVDs etc. That would eventually result in my long summaries on the UFC events. After I began BJJ in 2006, I soon found myself scouring the net for reading material, as well as picking up a few books (see my sources). Another summary seemed like a natural progression.

It has taken me a while to get enough books, internet articles and newspapers together that I felt I could do the subject of BJJ history any kind of justice, but there is still lots I'd like to read. Roberto Pedreira released some major contributions to BJJ research in 2014 and 2015, resulting in his three volume Choque. A similar (if less well referenced) release was With The Back On The Ground: those two books are probably the best I've seen in terms of serious BJJ history. The long-anticipated English translation of Reila Gracie's 2008 biography of her Carlos Gracie arrived in 2014, another useful source.

I'm also planning to add in details from the Black Belt archive, which might take a while. On top of that, I've been writing regular team history articles for Jiu Jitsu Style since 2010 and a broader historical summary for GroundWork, which have both helped bring up further details.

If anybody reading this has further historical resources, I'd love to hear about them. Any corrections are also welcome, as long as you can direct me to your source (i.e., a book, a reputable website etc). As ever, the below writing is based on Google, internet forums and the few English books available on the market, so it is certainly not definitive.

Origins ^

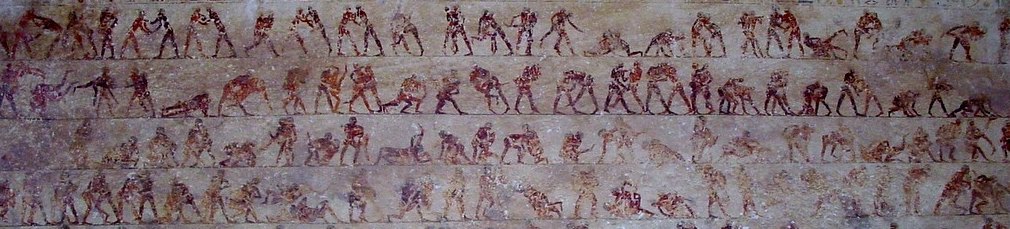

The history of jiu jitsu (note that this is just one of several spellings, but 'jiu jitsu' is what became standard in Brazil: more on that later) is comparatively long, but it is still far from being the oldest martial art. That title probably belongs to wrestling, in terms of the oldest documented system of unarmed combat. For example, murals from Beni Hasan in Egypt, made around 1950BC, demonstrate recognisable wrestling technique [1]

Still older are the limestone plaques and bronze jars, both depicting wrestlers, from Nintu Temple VI (in what used to be Sumeria, located in modern-day Iraq). These date from as far back as 3000 BC [2]. Boxing can also claim an ancient history: those plaques and jars I just mentioned feature boxers as well as wrestlers.

Jiu Jitsu is rather younger. Draeger and Smith write in Comprehensive Asian Fighting Arts that it had its beginnings in sumo, or more specifically, what they refer to as sumai ('combat sumo', and also the ancient Japanese word for 'struggle'). There are references to sumai in the Nihon Shoki, which talks of a fatal match between Tajima-no-Kehaya and Nomi-no-Sukune of Izumo in 23BC, won by the latter, but this may be apocryphal. [3]

A clearer date is 1532AD, when Takenouchi Hisamori founded his Takenouchi ryu (the Japanese term for 'school'), apparently based upon sumo. There is again the blurry surface of legend surrounding its origin. Draeger and Smith relate how the story goes that a yamabushi ('ascetic hermit') taught Takenouchi "five arresting techniques and showed him the advantage of shorter weapons over extremely long ones", which would eventually lead Takenouchi to form his own style. Draeger and Smith also state that some Japanese historians believe that it is from the Takenouchi ryu that all other jujutsu schools originate, though they also note that this is cast into doubt by the research of Fujita Seiko. [4]

John Danaher provides further detail in Mastering Jujitsu (cowritten with Renzo Gracie, the title using another variation of the style's spelling). He writes that in the Heian Period (794-1191AD), yoroi-kumiuchi (grappling in armour) developed out of sumo. This would form the basis for the classical military schools, or bugei, which emerged in the Kamakura Period (1192-1336AD). Finally, the Takenouchi ryu was founded in the Muromachi Period (1337-1563AD), against the backdrop of an increasingly militarised Japanese society, which had by now created the samurai aristocratic warrior caste. [5]

During the Edo period (1603-1867) there was a shift towards civilian training, as the various schools of jujutsu proliferated in more peaceful times. After the climactic battles at Sekigahara in 1600 and Osaka in 1615, Ieyasu Tokugawa had defeated the only other warlords powerful enough to contest the Shogunate, and could now consolidate his power over a unified Japan [6]. This also meant that the samurai became more engaged in bureaucracy than war: "education and culture came to replace military prowess as the chief concern of the samurai class" [7]. Instruction in combat was no longer as pressing an issue, so there was a shift to personal protection instead. As stated in Mastering Jujitsu, “within two generations, the emphasis was almost entirely on non-military technique.”

Jujitsu styles went into decline with the advent of the Meiji period (1868-1912), a time when everything seen as traditionally Japanese became stigmatised as unfashionably outdated. Danaher also points out that with the urbanisation of the population, competition was fierce, resulting in often bloody challenge matches to prove the superiority of a particular style. This meant that jujitsu acquired a reputation as "the activity of thugs and ruffians", which exacerbated the already decreasing interest in jujitsu. [8]

Jigoro Kano and the Foundation of Judo ^

Jigoro Kano, who would later become a hugely significant figure in the development of martial arts, was training in a number of jujitsu styles at the time. He was born in what is now the city of Kobe in 1860, the son of progressively-minded parents. As Mark Law writes, "In the new Meiji era, Kano senior was very much in the vanguard of those adopting the new outward-looking attitude and he sent Jigoro to prestigious and modern private schools. There Jigoro learned English, which was then unusual." [9]

Jigoro Kano, who would later become a hugely significant figure in the development of martial arts, was training in a number of jujitsu styles at the time. He was born in what is now the city of Kobe in 1860, the son of progressively-minded parents. As Mark Law writes, "In the new Meiji era, Kano senior was very much in the vanguard of those adopting the new outward-looking attitude and he sent Jigoro to prestigious and modern private schools. There Jigoro learned English, which was then unusual." [9]Kano was bullied at school, and like many after him, he sought martial arts as a way to defend himself. This would eventually lead him to Hachinosuke Fukuda, after Kano went to study at Tokyo Imperial University. Mark Law mentions an intriguing titbit at this point in his book, regarding Kano's attempts to overcome a much heavier sparring partner at his school. According to Law, Kano found his answer in a book on Western wrestling styles: the fireman's carry. Through diligent practice and private study, Kano was able to use this technique to finally master his larger opponent. The throw is still in judo today: Kano called it kata guruma (shoulder wheel). [10]

In John Danaher's summary, he states that Kano learned Tenjin-shinyo ryu for a two year period, until his teacher died in 1879. Kano then went to learn under Mataemon Iso, who unfortunately also died soon after, in 1881. Kano's next move was to Kito ryu jujitsu, which according to Danaher focused on throwing techniques. Finally, Danaher notes that Kano, having been an "extremely dedicated and innovative student", received the "symbol of leadership of Tenshin Shinyo jujitsu ryu – the written scrolls that depicted that system's history and technique." Presumably this is related to what Danaher earlier called 'Tenjin-shinyo', or simply a variant spelling. [11]

An educated man, Kano felt he could make improvements to the art. Danaher points out four main problems Kano sought to tackle: first, jujitsu's thuggish reputation; second, the lack of a set curriculum for both instruction and rank; third, an absence of overall strategy; fourth, inadequate training methods.

In order to solve these problems, Kano drew on his knowledge of jujitsu to create a new style. This style would not be simply concerned with skill (jitsu), but with a whole system of education, aiming to foster a code of ethics: in other words, a 'way' (do). Hence instead of jujitsu, Kano's style would be known as judo.

Kano brought in many changes to the traditional manner of training. One major development was the creation of shiai, a form of sanctioned competition. However, Kano's greatest contribution to martial arts was his approach to randori (sparring). He removed the so-called 'deadly' techniques from judo in order to enable live rolling. That had the end result of considerably increasing efficacy: because those early judoka could train 'non-deadly' (in the sense that you don't have to fully crank an armbar, lock on a choke etc, as your opponent has the option of tapping before serious damage) techniques full-contact, they became highly proficient, and in fact more 'deadly' than their non-sparring contemporaries in what might be called 'self-defence' orientated styles. As Danaher puts it, "the deadly techniques favored by so many traditional martial arts have only a theoretical deadliness with little practical deadliness." [12]

Judo, which at the time was known by a number of names, such as 'Kano ryu jujitsu', would prove itself through competition. Kano's school, which he had named the Kodokan ('house which shows the way', according to JudoInfo), faced a series of challengers from other schools. These men sought to prove that their style was pre-eminent, but to do so they would have to accept certain basic rules. As Danaher writes, Kano "wanted to avoid the undesirable image of jujitsu schools brawling in public, so all matches were held in the kodokan with limits on foul tactics and strikes."

The training methodology advocated by Kano meant that practitioners of judo dominated Japanese martial arts at the end of the nineteenth century. With an emphasis on high amplitude throws, judoka crushed the opposition time and again. This climaxed in the 1886 Tokyo police tournament, which had the intended goal of selecting a martial art to teach officers. Judo was the clear victor, winning thirteen of the fifteen bouts, the remaining two ending in a draw. Such levels of success eventually meant that the majority of top jujitsu stylists in other ryu, suitably impressed, switched to judo. No challenger seemed to have an answer to judo's apparently invincible strategy. [13]

No challengers, that is, except those from Fusen ryu. Unlike Kano’s Kodokan judo school, the Fusen ryu style was focused on groundwork, not high amplitude throws. Using a tactic which BJJ competitors might recognise from guard specialists, members of the Fusen ryu school immediately fell to their backs. The judoka's most dangerous weapon, their devastating throws, were negated in a clever tactical move. This meant that the limited groundwork of the Kodokan could be ruthlessly exploited by the skilful Fusen ryu fighters. [14]

It is worth noting that Danaher's account - my main source for the above comments on Fusen-ryu - is criticised by some in the judo community: for example, in this appraisal by Tactical Grappler on the JudoForum, the poster argues that Danaher's version "draws its conclusions too strongly based on too little evidence and conjecture". The importance of Fusen-ryu, according to such a view, may have been over-emphasised in Mastering Jujitsu.

However, from reading that JudoForum thread, it would appear that the consensus is that at least Mataemon Tanabe, the head of the school, had a high level of skill in newaza (groundwork, as opposed to 'tachiwaza', which relates to throws). If the JudoForum conclusion is correct, then the main flaw of Danaher's account would be attributing the abilities of one man to an entire style.

On the same thread, Joseph Svinth mentions that Danaher seems to have drawn heavily on Graham Noble's article about Yukio Tani: if you scroll down, you'll see a section related to Tanabe and Fusen-ryu. Noble quotes Kainan Shimomura, writing in the September 1952 edition of Henri Plée's Revue Judo Kodokan about the competition between the judoka Tobari and Tanabe:

The year after, he challenged Tanabe again. This time it was a ground battle and once more Tanabe won. […] The Kodokan then concluded that a really competent judoka must possess not only a good standing technique but good ground technique as well. This is the origin of the celebrated 'ne-waza of the Kansai region'. And in conclusion to all this one may very well say that Mataemon Tanabe, too, unconsciously contributed towards the perfecting of the judo of the Kodokan.

Either way, instead of angrily denouncing this new challenge, or fading from the public eye, Kano realised what Tanabe (or perhaps Fusen-ryu in general, if Danaher is right to emphasise that style's newaza at the time) had to offer. He sought to learn from Tanabe, eventually incorporating his style of grappling into judo. If the account in Mastering Jujitsu is correct, this was to prove of central importance to Brazilian jiu jitsu, as at the same time, a certain Mitsuyo Maeda had begun his training at the Kodokan. He would go on to travel the world, at first ostensibly to promote judo abroad, but later for more specific goals, such as helping Japanese settlers in Brazil.

[If you're interested in the history of judo and would like to find out more, I'd recommend you take a look at JudoInfo, which has a large number of articles, including those written by the man himself, Jigoro Kano]

The Gracie Family ^

In 1801, George Gracie emigrated from his native Scotland to the state of Para in north-eastern Brazil. The following century, George's descendant, a diplomat named Gastão Gracie, used his political influence to help Mitsuyo Maeda establish a Japanese colony in Brazil. In gratitude, Maeda offered to teach judo to Gastão’s sons: in The Gracie Way, only Carlos is mentioned as having learned from the judoka. [15].

Joseph Svinth cites rather different circumstances leading up to the meeting between Gastão and Maeda:

[16]

Wherever he was in 1916, Maeda was back in Brazil in 1917, where, according to Barbosa de Medeiros, he got a job with the Queirolo Brothers' American Circus. If true, then this is probably where Maeda met the Gracie family, as in 1916 Gastão Gracie was reportedly managing an Italian boxer associated with that same circus. (Less plausibly, but more grandly, the Gracies maintain that Maeda and Gastão met when both were representatives of their respective governments.) In any event, during late 1919 or early 1920, Maeda began teaching the rudiments of judo to Gastão's son, 17-year-old Carlos.

Maeda was known by several names. He is often referred to as 'Conde Koma', a name he apparently picked up in Spain during 1908. According to this review of one of the various biographies detailing Maeda's life, the name was essentially an alias designed to hide the already famous Maeda's identity from a man he wished to challenge. The review states that 'koma' comes from the Japanese verb 'komaru' (meaning 'to be in trouble'), suitable due to Maeda's financial woes at the time. 'Conde' is the Spanish word for 'Count': a similar story appears here. A somewhat different version is given on this site, which claims "For his elegance and good looks, always sad, Mitsuyo Maeda won the nick name 'Conde Koma' in México". He has also been called 'Count Combat', 'Conte Comte' (the Portuguese translation), Esai Maeda (such as in this history on Rickson's site) and according to Wikipedia, later took the name Otávio Mitsuyo Maeda.

Maeda was known by several names. He is often referred to as 'Conde Koma', a name he apparently picked up in Spain during 1908. According to this review of one of the various biographies detailing Maeda's life, the name was essentially an alias designed to hide the already famous Maeda's identity from a man he wished to challenge. The review states that 'koma' comes from the Japanese verb 'komaru' (meaning 'to be in trouble'), suitable due to Maeda's financial woes at the time. 'Conde' is the Spanish word for 'Count': a similar story appears here. A somewhat different version is given on this site, which claims "For his elegance and good looks, always sad, Mitsuyo Maeda won the nick name 'Conde Koma' in México". He has also been called 'Count Combat', 'Conte Comte' (the Portuguese translation), Esai Maeda (such as in this history on Rickson's site) and according to Wikipedia, later took the name Otávio Mitsuyo Maeda.It is worth noting here that while the name ‘judo’ has become the accepted term for Kano’s martial art, at the time many still referred to the style as ‘ju-jitsu’, or even ‘Kano ju-jitsu’. Maeda, like many others, had come to train under Kano having studied other ju-jitsu ryu previously (although some contend he only studied sumo). While the more usual Romanization is ‘jujitsu’, in Brazil the spelling ‘jiu-jitsu’ stuck, and has retained that extra ‘i’ ever since.

In addition, since leaving Japan, Maeda had become well known for prize fighting, which was frowned upon by the Kodokan. As Mark Law puts it, "amateurism had always been an essential part of the spirit of judo. Kano had decreed this." [17] By referring to his style as 'jiu jitsu' rather than 'judo', Maeda may have been attempting to avoid censure. Indeed, the later example of Masahiko Kimura, who was also involved in prize fighting, may lend further credence to the idea that the Kodokan would take action if a judoka participated in such events (for a related discussion, read this JudoForum thread).

John Danaher, writing in the historical introduction to Renzo's earlier book, Brazilian Jiu Jitsu: Theory and Technique, appears to agree:

Maeda was a world traveller. After his time in North America he toured Central and South America and also Europe. By taking many professional challenge fights, Maeda clearly went against the strict moral codes of Kodokan judo. Probably because of this, Maeda described his fighting method as "jiu-jitsu" rather than "judo."[18]

There are other likely reasons why he switched the nomenclature of his art. Maeda had in fact studied classical jiu-jitsu before he studied judo under Jigoro Kano […]. When he began fighting challenge matches, he almost certainly began using techniques that were not allowed in judo training but which were part of his old jiu-jitsu curriculum. […]

One thing is clear, when Maeda taught people during these long overseas voyages, he insisted on calling his art "jiu-jitsu".

A common theory that crops up on internet forums is the alleged link between Brazilian jiu jitsu and Kosen Judo. For example, in Mark Tripp's long history of judo and BJJ, he claims that Maeda "had some connection to the Kosen Judo program, "a type of judo taught in public schools which focused on groundwork. Tripp bases this on Osaekomi by Katsuhiko Kashiwazaki, from which he then quotes:

At this time newaza was extremely popular and well researched, particularly by the Kosen Judo students. This was because Kosen Judo was an inter-school team contest only, so there was the possibility to draw. This was a time of only one score: IPPON or a draw. Most of the students participating were beginners, so in a very short time they had to develop players who could compete. For this reason newaza training was very useful. It was easier to get draws in newaza so they researched turtle positions, double leg locks, and so on extensively.

As Tripp notes, 'double leg locks' was effectively the same as what is now known as the guard position. Kosen Judo, in other words, was similar in many ways to what became BJJ: indeed, Tripp goes so far as to say that "todays BJJ/GJJ players have a more direct route to Kano than the current crop of "Sport Judo" fighters! Current Judo people have ONLY seen what the IJF rules say Judo is, and that AFTER the MacArthur ban (something Brazil didn't have to deal with)."

The main problem with this argument is that the Kosen ruleset was introduced into the Japanese school system in 1914, several years after Maeda had left the country, which would therefore make the above theory impossible. This is an extract from the history posted on the Kyoto University Judo Club website:

In Taisho Era (from 1912 to 1926), Kyoto University Judo Club played an important role in Japanese Judo and gave lots of influence to it. In Taisho 3 (1914) the Judo Competition of Higher schools and Colleges (Kosen Taikai) was commenced in Kyoto under the sponsorship of Kyoto University Judo Club at Butokuten (the name of the place where the competition was held). Year by year this Kosen competition grew bigger and bigger and had many participants all over Japan. In the Kosen competition, we did not have any restriction on practicing "Newaza" (ground work), so that we could fight under the rule of admitting "Hikikomi". Owing to this rule Newaza prevailed all over Japan.

Maeda had numerous Brazilian students. If that included Luiz Franca, as some claim, he is another notable figure: his lineage would include men like Oswaldo Fadda (as per the Onzuka brothers extensive historical summary, here). Others have suggested that Maeda was not the first Japanese martial arts instructor in Brazil. In a Global Training Report article, Moises Muradi points to a teacher named Miura arriving in 1903, over a decade before Maeda. In the first volume of Choque, Roberto Pedreira states that Sada Miyako and a 'Mme. Kakiara' were the first confirmed Japanese fighters to arrive, on 16th December 1908 (to be specific - and thankfully for researchers, Pedreira almost always is - they disembarked at 1am).[18a] Pedreira also points to Mario Aleixo, a Brazilian national who he states had been teaching jiu jitsu since 1913 at the Centro do Sportivo do Engenho Velho.[18b]

On page ninety of his thesis, Jose Cairus notes that Carlos Gracie may have trained under an earlier Brazilian student of Maeda, called Jacyntho Ferro. A local wrestler, Ferro began studying with Maeda in 1915, and Cairus states that Ferro was recognised as "Count Koma's most complete student," pointing to interviews from Folha do Norte on the 4th August 1920 and 14th December 1923. Pedreira makes an even bolder claim: Carlos was never a regular student under Maeda. Pedreira argues that while Carlos may have taken a few lessons with Maeda,[18c] it is much more likely Carlos learned from Maeda's student, Donato Pires dos Reis. [18d]

However, whether or not the Gracie family were the first Brazilians to learn from Japanese martial artists, they were definitely the most successful at marketing their system, so it is their name which looms largest in later history. There is some disagreement about just how long Carlos trained under Maeda (assuming he ever did): Carley Gracie, one of Carlos' sons, claims that his father began at 17, opening his first academy four years later in Belèm. [19]

Kid Peligro, a close friend of the Gracies, claimed in The Gracie Way that Carlos studied judo (which he would have referred to as 'jiu jitsu') from the age of fifteen until he was twenty-one. In 1925, Peligro writes that Carlos and his brothers moved to Rio de Janeiro, where again Carlos allegedly opened a school. By this time, Gastão had fallen ill, leaving Carlos to care for his younger brother, Hélio: there was an eleven year age gap between the siblings. [20]

In order to publicise his new academy, Carlos is supposed to have taken out an advertisement in the largest newspaper in Brazil, proclaiming “If you want a broken arm or rib, contact Carlos Gracie at this number.” Whether this advert was really presented in that fashion (Pedreira believes it may be an apocryphal story), the impetus behind it has since become known as the Gracie Challenge, and would prove to be an integral part of BJJ’s growth. According to the official history, Carlos initially represented the family, but later on – and contrary to expectation – his younger brother Hélio would become the Gracie’s champion.

Here again Choque has a different version of the story. Pedreira draws upon newspapers from the time to suggest that Carlos did not found a Rio academy in 1925. Instead, some years later, he took over the academy of the man Pedreira believes was his main instructor, Donato Pires dos Reis. Both Carlos and George were listed as assistant instructors at Pires dos Reis' Academia de Jiu Jitsu[20a], which Pires dos Reis opened on rua Marquez de Abrantes n.106 in 1930.[20b]. By December 1931, Pires dos Reis had either left or been pushed out: his old school was now being referred to as the Academia Gracie.[20c]

Hélio, the youngest Gracie brother, was supposedly a sickly child. This is an important part of the powerful Hélio Myth popularised by his eldest son, Rorion. Hélio is described by Kid Peligro as possessing “so weak a constitution that he couldn’t even go to school because he suffered from spells of dizziness”. As he was allegedly so frail, Hélio did not take part in his brother’s jiu-jitsu classes. Reila Gracie fleshes out this perception of her uncle as a weakling:

Of Gastão and Cesalina's male children, Hélio was the chubbiest and most robust in his early life, earning him the childhood nickname 'gordo,' or 'fatty,' among family. From the ages of 9 to 15, however, he became thin, fragile and apparently unhealthy. He suffered from dizzy spells and often fainted at school. The family doctor couldn't identify a specific health problem but recommended that Hélio avoid all physical activity. The lack of dialogue between parents and children, typical of the times, meant he had no way of expressing his opinions and dissatisfaction, which is probably why it didn't occur to either the family or doctor that his blackouts were due to emotional causes. The move to Rio de Janeiro, the family's financial instability and his father's absence were all enough to rattle him.[20d]

Whatever the extent of this apparent condition, the claim is that due to an inability to take part, Hélio watched instead. According to the man himself in The Gracie Way, just how closely Hélio was paying attention became clear one day, when Carlos was late for a private lesson he was due to teach. While Carlos' student waited, he asked Hélio if he wanted to ‘play’: once Carlos finally arrived, that ‘play’ had convinced the student that he wished to learn from Hélio instead.

Many people unsurprisingly feel that this is an exaggeration, as it would seem rather unlikely a person could - through mere observation - master a martial art to a high enough level that they could then teach it. A rather more plausible version of events is related by Reila Gracie in the hefty biography she wrote about her father:

Jiu jitsu required trained reflexes and, no matter how brilliant or talented he was, in order to truly master the technique Hélio would have to practice his moves with someone. Because he was no longer in school, he had all the time in the world to spend at the academy. He started taking lessons from Gastão Junior and practicing with George and the other students. When Carlos noticed, he decided to turn a blind eye, giving him the space to learn however he pleased. Little by little, Hélio was initiated in jiu-jitsu and was soon intimate with it.[20e]

Claiming that he lacked the physique of a well-conditioned athlete, Hélio insisted he had to find another way to make judo/jiu jitsu work for him. This again does not ring true, given that the Japanese are not known for being huge and muscular, especially not judo's founder, the diminutive Jigoro Kano. It is therefore rather dubious to imagine judo relies on strength rather than leverage. Nevertheless, Hélio told Kid Peligro:

I couldn’t do most of the moves, but I strived hard to find ways to adapt them to my abilities. All my life I have been very determined, and I took it as a challenge to find ways to do the moves. So I began experimenting with different leverages and adjustments…I started to study the leverage points on the human body. If you use leverage, you can multiply your effect many times over, much like you use a jack to lift a car. You can’t lift a car, but when you use a jack you can easily lift it. I simply adapted the use of a “jack” to every position of jiu-jitsu. And that became the sport we have today. I made the sport accessible to the weakling so he could defend against a strong personCarlos soon realised his brother’s talent for teaching, and therefore left much of the instruction to Hélio (particularly as Carlos had fallen out with the more talented George). The younger Gracie took charge of forty twenty-minute private lessons a day, which gave Carlos the time to focus on managing the academy. [21]

Hélio also began taking on challengers. His first was a boxer, Antonio Portugal, when Hélio was seventeen years old. According to Hélio in The Gracie Way, the fight was over in thirty seconds, Portugal succumbing to an armlock. Through his fighter, which swiftly spread throughout the Brazilian media (along with those of George, his more respected brother), Hélio brought the Gracie take on judo/jiu-jitsu to a national audience, further enshrining the use of 'jiu-jitsu' to describe what they taught. In addition, as Kid Peligro points out, by issuing and accepting so many challenges, the Gracies were pressure testing their style. If any technique failed in the unforgiving environment of a real fight, it was either thrown out or modified, ready for the next test. [22]

The Gracies were a large family, and while Hélio and Carlos are by far the most well-known, their brothers would also become teachers of jiu-jitsu: for example, Jorge Gracie (also often referred to as George Gracie) was a talented instructor. Eduardo Pereira, one of his students, describes in a Global Training Report article how Jorge also fought in challenge matches. Pereira believes that Jorge "did as much as his brother Hélio to elevate the name of the 'gentle art'…but being excessively modest and introverted, he did not become as famous." Carley Gracie states that Jorge, Osvaldo and Gastão Jr all learned from Carlos, Hélio being the last brother to learn jiu-jitsu [23]. Osvaldo also provides a classic example of the smaller man using jiu-jitsu to overcome a much larger opponent: "Osvaldo Gracie, who weighed 140 pounds, fought John Baldy, who tipped the scales at 360 pounds. Osvaldo defeated Baldy with a choke hold in just two minutes." [24]

Choque goes into considerable detail about this period of jiu jitsu's development. According to Pedreira, the Gracies were far from the only jiu jitsu/judo fighters in Brazil at the time. They were preceded not only by Maeda, but other Japanese nationals like Geo Omori. Other superior fighters followed, like the Ono brothers and Takeo Yano. The record of the Gracie family has also been exaggerated, if Pedreira's research is accurate. He states that Carlos only ever had two legitimate fights, a loss to Manoel Rufino[24a] and a draw with Geo Omori.[24b] He had an earlier encounter in the ring with Geo Omori in 1929, but that was merely an exhibition match. Carlos, drawing on the marketing skill which has served his family well ever since, pretended it was a real fight, much to Omori's irritation.[24c] The 1930 encounter was genuine, where Carlos managed a respectable draw with the experienced Omori. It would be the best performance of his short career, leaving Carlos with a record of 0-1-1.[24d]

Hélio's record was better than his elder brother's, but still mostly consisted of draws. His most famous contest was with Masahiko Kimura, a prodigiously talented judo champion. Their fight has passed into legend, and as tends to be the case with legends, several of the facts change depending on who you ask. The basic uncontroversial elements are that Kimura was in Brazil in the 1950s with two other top judoka, Kato and Yamaguchi. According to Kimura himself, in the excerpt from his out-of-print autobiography My Judo, posted on JudoInfo.com (although it should be noted that the translator, pdeking, has been accused of intentionally spreading misinformation):

Hélio's record was better than his elder brother's, but still mostly consisted of draws. His most famous contest was with Masahiko Kimura, a prodigiously talented judo champion. Their fight has passed into legend, and as tends to be the case with legends, several of the facts change depending on who you ask. The basic uncontroversial elements are that Kimura was in Brazil in the 1950s with two other top judoka, Kato and Yamaguchi. According to Kimura himself, in the excerpt from his out-of-print autobiography My Judo, posted on JudoInfo.com (although it should be noted that the translator, pdeking, has been accused of intentionally spreading misinformation):I went to Brazil by the invitation of Sao Paulo Shinbun [local Japanese newspaper company in Sao Paulo]. Sao Paulo Shinbun, which was in a slump, came up with an idea of doing pro wrestling to revive their business. The period of contract was four months. The participants were I, Yamaguchi and Kato, fifth dan. This enterprise was a big success. Wherever we went, the arena was super-packed. This made President Mizuno of Sao Paulo Shinbun very happy. When we asked for a pay raise, he tripled our original pay on the spot. In addition to pro wrestling, we gave judo instruction wherever we went.The two men first fought to a gruelling thirty minute draw, then in a rematch, Gracie defeated Kato by choke on the 29th September 1951. That meant Yamaguchi was next in line to face the Brazilian, but he told Kimura he was concerned over the rules. To turn again to My Judo:

One day, Helio Gracie, judo sixth dan, issued a challenge to us. The rule of the bout was different from that of judo or pro wrestling. The winner was decided by submission only. No matter how cleanly a throw is executed or how long Osaekomi lasts, it does not count. He issued a challenge to Kato first.

If he fought a judo match under the Japanese rules, Yamaguchi is superior to Helio both in tachi-waza and newaza. But under the Brazilian rules, if Helio got pinned on the ground, all he has to do is to stay calm and be cautious not to get caught in a choke or joint lock, and remain still till the time runs out. Helio could fight to a draw in this way. If he used these tactics, it would be difficult for Yamaguchi to make Helio surrender. I then said to Yamaguchi, "Do not bother to come up with a plan to make Helio submit. I will accept the challenge."The conditions, according to The Gracie Way, were that if Hélio could last three minutes, Kimura would consider him the winner. This was largely due to the weight difference, one of the controversial elements of the story which has shifted over the years. In The Gracie Way, Kid Peligro writes that Kimura "weighed 220 pounds [99.7kg] to Hélio's 154 [69.8kg]" [25]. This contradicts Kimura's account in My Judo, as he states there that "Hélio was 180cm and 80kg [176lbs]." On the JudoForum, one poster claims that "I did a little research and found that Kimura weighed somewhere in the neighborhood of 185lbs [83.9kg] and stood 5'6."

This is also backed up by Kastriot "George" Mehdi, a long-time critic of the Gracies (but also an exceptional judoka and teacher, who has taught Rickson, Carlson Jr and Sylvio Behring, among others). Mehdi once spent some years training under Kimura, and states in Roberto Pedreira's article that Kimura was far from the 100kg often claimed by the Gracies. He showed Pedreira a picture of Mehdi and Kimura at around the time of the fight: Mehdi was 5'9 and 80kg, and according to Pedreira, the photograph makes it clear that the two men looked physically comparable, in terms of mass and height. Therefore it would appear that Hélio was certainly smaller than Kimura, but it remains unclear exactly how much.

On the 13th October 1951, the two men faced off, putting Hélio on the receiving end of a painful thirteen minutes. Mehdi goes so far as to claim that "Kimura agreed to stall for 10 minutes to give the fans their money's worth and begin fighting after that." Whether or not there is any truth to this controversial claim (Mehdi's dislike of the Gracies is well-known), Kimura would eventually secure a solid armlock on his opponent. The stubborn Brazilian still refused to submit: Carlos had to throw in the towel to save his brother from serious harm. Kimura's description in My Judo sounds especially brutal:

I applied ude garami. I thought he would surrender immediately. But Helio would not tap the mat. I had no choice but to keep on twisting the arm. The stadium became quiet. The bone of his arm was coming close to the breaking point. Finally, the sound of bone breaking echoed throughout the stadium. Helio still did not surrender. His left arm was already powerless. Under the rules, I had no choice but twist the arm again. There was plenty of time left. I twisted the left arm again. Another bone was broken. Helio still did not tap. When I tried to twist the arm once more, a white towel was thrown in. I won by TKO.Hélio had lost the fight, but had more than achieved the stated goal of surviving three minutes. In honour of the judoka's skilful victory, the armlock (ude garami in judo) which had beaten Hélio was thereafter known as the Kimura in Brazil, a name which has stayed with BJJ up to the present day. [26]

There is footage of the contest (you can also find the earlier match with Kato online) too), though as this is YouTube, it may go down. Let me know if that happens and I can replace it:

Hélio would take a much deserved retirement not long after his loss to Kimura, but was forced back into the ring by the actions of one of his students, Waldemar Santana. Santana had been a top student and instructor at the Gracie Academy for the preceding five years, but was not a wealthy man. He was therefore tempted by the prospect of making some cash fighting at the Palacio de Aluminio, which according to Kid Peligro was "a show house for fake matches". Hélio refused permission, saying that it would tarnish the reputation of his Academy, but Santana needed the money so went ahead with his match. [27]

This would eventually lead to a fight between Santana and his former teacher. For an agonizing three hours and forty-five minutes, the combatants fought without a break. The heavier, younger Santana would at last overcome Hélio, through a combination of the latter's exhaustion and a kick in the face (Hélio was also apparently still suffering from a lingering illness). [28]

Carlson and Rolls ^

One of Carlos Gracie's sons, Carlson (born on 13th August 1935), would take up the position of family champion after the Santana fight. Carlson reclaimed the Academy's honour by defeating Santana himself in 1956. As he related to Kid Peligro:

Waldemar Santana was actually a good friend of mine. We liked each other, but after the fight with my uncle Hélio I called him and told him that we now had a problem. So I challenged him to a fight and said, ‘I am your friend, but in the ring we are enemies and I am going to beat you to a pulp!’ Because I was underage, my father had to forge some papers stating that I was twenty-one years old so that I could legally fight.[29]

This victory massively raised Carlson's profile, and laid to rest any doubts Santana's defeat of Hélio might have raised with the general public. The Gracie family were once again the undisputed champions of Brazil, with a burgeoning school. Indeed, the numbers became so large by 1968 that Carlson decided it was time to open his own academy. As he told Kid Peligro, “[Hélio and I] didn’t fight or anything, it just got to the point that I needed my own space. I also wanted to implement my own style of teaching, and that created more friction with my uncle, so it was best that I opened my own school.” [30]

The new location was in Copacabana, on Avenida Nossa Senhora de Copacabana, above the Gebara store. Carlson later opened two more academies, first in Niteroi, then back in Copacabana. He brought in his brother Rolls to help with teaching, and it was this third school, at Rua Figueiredo Magalhaes 414/302, which would prove the most lasting. Carlson would eventually concentrate all his teaching there, initially alongside Rolls.

Though Rolls learned from Carlson's more aggressive, physical style, Kid Peligro relates that Rolls decided he wanted to "implement the technical teaching style of Hélio," so they separated their classes. Keeping the same location, the two Gracies agreed to rotate between the upper and lower floors, because upstairs was a higher quality room. A system was set up where Rolls taught upstairs on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, while Carlson would teach there Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday.

Kid Peligro emphasises just how pivotal this period proved to be. Indeed, he writes in The Gracie Way that Carlson's move to a new academy "cannot be overlooked as one of the key moments in the development of modern Brazilian jiu-jitsu." He goes on to quote Carlson, who told him "I was one of the revolutionaries because I opened jiu-jitsu to the public. At the main school they were much more closed and didn’t share their techniques."

In addition, Carlson was a driving force behind the growth of competition: now that instructors were beginning to branch out on their own rather than all staying within the same academy, a healthy rivalry could act as a catalyst to progress the art of BJJ. [31] Carlson's contribution to BJJ, and competition in particular, would not end there, continuing right up until the end of his life in February 2006 – his name will crop up again in later sections of this history.

Rolls has since acquired a legendary status, seen as perhaps the most talented technician to ever hold the Gracie name. Born on the 28th of March, 1951, Rolls was the son of Carlos Gracie and Claudia Zandomenico, an Italian stewardess. Carlos' wife was not especially keen to be reminded of her husband's children with other women, so Carlos asked his brother Hélio to raise Rolls instead. Romero 'Jacare' Cavalcanti believes that this was the foundation of Roll's great skill. “He would train with Hélio privately and got so technical that it was unbelievable […] [Hélio's] knowledge of position and techniques was incredible. But he was so small that he couldn’t rely on strength. Rolls learned all the refined technical skills under Hélio, much as later on Rickson and Royler did.” [32]

Kid Peligro suggests that Zandomenico's job with Lufthanza broadened her son's horizons, as it meant he could travel for free, leading to numerous trips to Europe and the United States. [33] This was perhaps why Rolls became receptive to outside influences, eager to absorb what he could of other cultures, an impulse that extended to martial arts: for example, Rolls cross-trained in judo with Osvaldo Alves, on the advice of his brother Reyson. As Cavalcanti remembers:

Rolls was always so open-minded, constantly seeking to improve his game and jiu-jitsu in general. He trained with Osvaldo almost daily for one year. Osvaldo introduced Rolls to the hard training that he had learned in Japan, like running on the beach and practicing throws. After one year of improving his strength and conditioning, along with his stand-up skills, Rolls returned to Carlson's school and was light years ahead of everyone.[34]

1978 provided Rolls with a perfect opportunity to further develop his grappling knowledge, as that was the year wrestling coach Bob Anderson came to Brazil. Anderson had been sent by FILA (Fédération Internationale des Luttes Associées, or 'International Federation of Associated Wrestling Styles') in order to help the Brazilian Wrestling Federation. However, according to Kid Peligro, the Federation failed to send anyone to the airport to greet Anderson on his arrival.

Rolls and Robson Gracie were more than happy to intercede. Anderson didn't realise who they were, so continued under the impression that these must be the representatives from the Brazilian Wrestling Federation. Neither Gracie had any intention of correcting him, so a week passed with Anderson training and teaching with Rolls. The Brazilian eventually admitted that he had nothing to do with the Federation: "I just wanted to learn wrestling". By that point, as Peligro writes, Anderson had already built a close friendship with Rolls, and was happy to help despite the somewhat unusual circumstances. [35]

It is from this exchange of knowledge that several additions were made to Brazilian jiu jitsu. Much like the Kimura armlock had emerged from Hélio's fight with the Japanese judoka, the Americana also came to BJJ from outside the art. Anderson remembers:

Rolls and I would be brainstorming. He would bring one of the students and put him in a position and ask me what I would do to get him on his back or something. One time I showed him what I would do to get an arm bar when the student was all rolled up in a ball. I did what we call a ‘turkey bar’ and he liked it. [36]Rolls would later visit Anderson at his home in San Clemente, California. The two of them travelled to the AAU National Sambo Championships and then the YMCA National Sambo Championships, where both men won their divisions. "Rolls kicked butt in both of them," remembers Anderson. "He just walked through the tournament and destroyed everyone." [38]

He called it the Americana because I was the American wrestler that came down and showed him the move. [37]

Sadly, Rolls' enormous potential would remain unrealised. On 6th June 1982, he died after a hang gliding accident in the mountains of Mauá, Brazil. [39] According to one of his students, Carlos Valente, Rolls was a teacher of a different order:

Rolls Gracie was a father. Rolls Gracie was beyond a regular instructor. He was beyond any regular instructor in martial arts. You have the vision of the tough guy, and the respect for his black belt, but Rolls’ energy, his aura that can touch your soul in so many ways, that I don’t see in many Gracie family members, except after he died, Rickson Gracie is the only one that has the energy that can touch your mind, the mental and your soul. […][40]

If you can spend time with Rickson, if you can spend one day with Rickson, it will last you one or two years. Whatever he has to say to you, whatever his energy. You know, Rolls had the same thing. Rolls is a guy, that, let’s say we had people on the mat… forty guys left… Monday night was the toughest night and Friday night. Lotta people talking bla bla bla bla. Rolls walked in and: silence. But not as fear, but respect.

Yet despite Rolls' death, his legacy would continue through his hugely influential students. The most important is arguably Carlos Gracie Jr, often referred to as Carlinhos. It was to him that Rolls' wife turned after that terrible day in 1982, telling him "You are the right person to take over; even Rolls told me that you would be his successor." At the time, Carlinhos was happily teaching full-time from his home, but took on the heavy mantle of following in Rolls' shadow, returning to the hustle and bustle of Copacabana.

Two years later, he was able to escape the crowds and noise by moving to what was then a small town, Barra da Tijuca. As he was not the only Gracie training there, he decided against the obvious name of Carlinhos Gracie Academy. Instead, he named it after the location: Gracie Barra. From that one school, Gracie Barra has become an enormous organisation that spreads across the world. [41]

Romero 'Jacare' Cavalcanti ('Jacare' means 'crocodile' in Portuguese) also went on to found a powerhouse BJJ team, Alliance. He received his black belt from Rolls himself just four months before the legendary instructor's death, a rare distinction he shared with a mere five other men. Like Carlinhos, Cavalcanti's organisation has also gone global. Alliance spawned further teams of its own, such as Brasa, TT, Checkmat and Atos.

Then, of course, there is Rolls' brother Carlson Gracie, whose team went on to great success in both BJJ and MMA. Like the others, the Carlson Gracie name can be seen above gyms around the world. As with Alliance, there were also splinter groups, such as Brazilian Top Team, but the Carlson Gracie team continues to be a major force in BJJ. His student Rodrigo Medeiros is the main figure responsible for carrying on the Carlson name (under the BJJ Revolution Team banner), after his mentor passed away in 2006.

Had Rolls lived longer, perhaps this cosmopolitan, open-minded Brazilian might have been the Gracie to first bring Brazilian jiu-jitsu to the rest of the world. His early death meant that task would have to be taken up by others: the venture would eventually prove a great success. It was from the United States that BJJ would grow to become a global phenomenon.

BJJ Comes to America ^

Carley Gracie was the eleventh child of Carlos, and the first member of the family to run a school in the US. He states in a 1994 interview that he arrived there in 1972, invited by the United States Marines to teach them jiu-jitsu. This had evolved from an earlier stint instructing a group of Marines at the American consulate in Rio de Janeiro. Carley claimed that since 1972, he had "taught the Gracie style of Jiu-Jitsu in Virginia, Connecticut, Maryland, Florida and California, where I have lived and taught Jiu-Jitsu since 1979". [42]

Yet it was another Gracie, Rorion, who truly established the style in North America. Kid Peligro writes that Rorion first arrived in 1969, as a seventeen year old. After teaching a few jiu-jitsu lessons, his money and return plane ticket were stolen from the Hollywood YMCA. Rorion suffered through a stint sleeping rough on the streets, eventually making it back to Brazil, where he continued to teach. He also entered university in Brazil, earning a degree in Law. [43]

In 1978, six years after Carley, Rorion decided to try heading north for a second time. He started out teaching a small group of students from his garage. As he told Kid Peligro, "when I mentioned that I taught jiu-jitsu, sometimes people would say they knew about it, thinking it was all the same. So I coined the term Gracie jiu-jitsu to set apart my family's style." In addition, he upped the Gracie Challenge to $100,000, an effective marketing ploy. [44]

Just like in Brazil many decades earlier, the Gracie Challenge would be an integral part of the Academy's growth. Sometimes that would be in a very direct sense, as Todd Hester (who began training with Rorion in 1988) remembers in his interview on Eddie Goldman's podcast, No Holds Barred:

I used to go to some of the early Gracie challenge matches, you know, before the UFC. Guys would come in and put some money down in a back room, and the Gracies would put money down, then they'd just fight [...] The thing I really noticed is that after the fight, a lot of times, the Gracies wouldn't even take the money, and the guys that they beat would end up becoming their students.[45]

As Clyde Gentry describes it in his book on the history of mixed martial arts (which coincidentally, like Goldman’s podcast, is also called No Holds Barred), the Gracie Challenge took off in America when Benny ‘the Jet’ Urquidez got involved. The Jet, a legendary kickboxer, was willing (at least at first) to back up a karate instructor friend of his who had agreed to fight Rorion. However, Urquidez decided against following through after a friendly sparring session with Rorion demonstrated the efficacy of the Brazilian's grappling. A second opportunity arose when a documentary film crew contacted Rorion, hoping to set up a challenge match with a kickboxer: the man in question turned out to be Urquidez. [46]

Wrangles over rules meant the match fell through a second time, but did create sufficient hype that would eventually lead to Rorion choreographing a fight between Mel Gibson and Gary Busey in 1987’s Lethal Weapon. Gibson, playing a maverick cop, decides to offer the special-forces-operative-turned-criminal, played by Busey, a chance to fight him instead of arrest. Their scuffle in the rain features a classic BJJ submission: the triangle choke (on YouTube, of course, though that video may disappear at some point).

The following December, a small advertisment appeared in Black Belt magazine, promoting a tape called Gracie Jiu-Jitsu in Action. The tag line promised "Real Fights, Original Footage", with a quote from Chuck Norris informing prospective customers that "The Gracie Brothers are the best at what they do. This tape is a must see". Rorion provided the commentary over various fights demonstrating the efficacy of Gracie jiu jitsu: the heavy bias has been criticised in the years since, but tales of GJJ's invulnerability helped launch the style in the US. The mail-order tapes became a catalyst for spreading the Gracie name, and in particular, making the Gracie Challenge a major part of BJJ's appeal to US residents looking for a proven system:

Further exposure came with Don Beu's article in Black Belt in August 1989, but it was the following month's Playboy that really brought Gracie jiu jitsu to widespread attention. Pat Jordan contributed a piece entitled ‘BAD’, in which he dubbed Rorion Gracie “the toughest man in the United States”. Jordan described Gracie jujitsu as “a bouillabaisse of the other martial arts: judo (throws), karate (kicks, punches), aikido (twists), boxing (punches) and wrestling (grappling, holds)”, though he could have more simply defined it as judo with a highly refined focus on groundwork. Jordan also provided one of the early citations of the “most real fights end up on the ground 90 percent of the time” statistic, which would be oft-repeated in later years. [47]

Jordan’s article generated plenty of interest among Playboy readers, along with a follow-up on the Gracie Challenge in Karate Kung Fu Illustrated. Arthur Davie, who worked for advertising firm J & P Marketing, was one of those readers. He thought he saw business potential in the Gracies, leading him to travel down to the half-built Gracie Academy in Torrance, California during 1990. There he saw Royler Gracie engage in a challenge match, easily despatching his karate trained opponent. This inspired Davie to take lessons himself, making friends with fellow student, film director John Milius, in the process. [48]

Numerous members of Rorion's family came over to join him teaching out of his garage, moving permanently to various parts of the United States over the years. In 1983, his seventeen year old brother Royce, who spoke no English at the time, came to Torrance to help with instruction. [49] In 1985, Relson established a school in Hawaii, moving to the Islands permanently three years later. [50] Rickson came to California in 1989, with four schools in Southern California by 1995. [51] Then there were the Machado brothers, who had also come to Torrance to help their cousins.

The Machados were not only cousins to Rorion and his brothers, they had learned alongside them from Hélio and Carlos, at the enormous Teresopolis mansion. They are also yet another lineage whose origins can be traced back to the Rolls and Carlson school in Copacabana, as the Machados trained with Carlinhos at Gracie Barra. He was the man who would eventually give them their black belts, but as he said in a 2002 interview, "They could use the Gracie Barra name. They prefer to use their own name, Machado, also a strong name in Jiu-Jitsu. It's ok; it's good for them."

Like Rorion, the Machados would also make connections in Hollywood. According to Black Belt Magazine, Carlos Machado, the eldest of the brothers, met Chuck Norris while on vacation in Las Vegas during 1988. Norris was running an event there, the United Fighting Arts Federation Convention. [52] The Los Angeles Times emphasised a different brother, Rigan Machado, who had apparently met Norris in 1989, while scuba diving. [53]

Cesar Gracie was another important figure around at the time, as he discusses on Fightworks Podcast. Cesar remembers how in 1990, he brought the Machados to Redondo Beach to teach out of his garage, later also bringing over another relative, Ralph Gracie. The sheer size of the Gracie family was undoubtedly an important factor in their later success.

Chuck Norris was impressed by what he saw of BJJ, deciding to take up the art himself (he would later earn a black belt in the style). In 1991, Norris encouraged Carlos, John and Rigan to open up their own school in Encino. Carlos Machado had previously been helping out at the Torrance academy, but according to Gentry, had aggravated Rorion. Hélio's eldest son claimed that "the Machados began teaching students behind his back, as well as undercutting his prices and changing the way the art was taught." Judging by Cesar's comments on teaching in 1990, Rorion may have been referring to Cesar's garage in Redondo Beach. Either way, this apparently lead to a lawsuit over use of the Gracie name, a practice for which Rorion would become infamous. [54] Nevertheless, helped by Norris’ influence, the Machado's new academy got plenty of attention, it’s success enabling Rorion's cousins to open up a second school in December 1992, located over at Redondo Beach. [55] In that same year, a major landmark for American BJJ was reached: Craig Kukuk became the first American to receive his black belt, from Royler Gracie (as per a now defunct NHB Gear thread [http://www.nhbgear.com/forum/index.php?topic=60940.0]), while the Royler lineage is mentioned in another defunct NHB Gear thread [http://www.nhbgear.com/forum/index.php/topic,16964.msg216467.html#msg216467]. Kukuk would also produce a seminal instructional series with Renzo Gracie in 1994 (full review here).

Gracie Jiu-Jitsu in Action had been a success since it was first advertised in 1988, demonstrating how tapes could be an effectives means of raising GJJ's profile. In 1991, Rorion returned to the video medium, this time releasing an instructional series, Gracie Jiu Jitsu Basics (my review, with more historical details and context, here). Gracie Jiu Jitsu was largely limited to the Gracie Academy in Torrance in the early '90s, though several black belts - such as the aforementioned Machados - were beginning to branch out on their own. With a tape series, Rorion could reach potential students far beyond California, not to mention make a tidy sum from video sales. There was also the possibility that customers who were learning by tape might be sufficiently inspired to seek instruction from the Gracie Academy itself: if nothing else, those tapes did much to increase interest in grappling.

The Gracie Challenge was seen by some as arrogant, such as William Turner, who claimed that the Gracies were somehow failing to "instill confidence and proper social behaviour in others while developing the warrior spirit." In his November 1990 letter to Black Belt, he argued that the challenge should be withdrawn. Rorion Gracie himself responded a few months later, in the process setting out his reasons why the Gracie Challenge was important:

[56]

The Gracie challenge is a belief that we are indeed teaching the best system in the world. Consequently, we have a moral responsibility to ourselves, as well as our students, to keep the Gracie challenge standing. The fact is, we are not cocky or boastful like some jealous characters describe us, but instead we feel the need to alert people interested in finding out about a truly effective form of self defence. They can use the Gracie challenge to put pressure on their incompetent instructors, who should have the dignity and courage to admit how limited their systems really are. Unless, of course, those instructors want to step forward and prove us wrong

This mixture of marketing and bravado was typical of Rorion, and a large part of Gracie-Jiu-Jitsu in Action as well as Gracie-Jiu-Jitsu in Action 2. He never missed an opportunity to insert an advertisement for GJJ in the midst of commentating on the fights. While this does make the tapes feel like an extended sales pitch, the fights themselves were nevertheless firm evidence of GJJ's efficacy, despite the bias which led to some dubious interpretation of events (such as the controversial perspective on Kimura's victory). Rorion presented himself as "the head of the Gracie family", a role he very much took to heart. Rorion was extremely protective of his family's style, most famously exemplified by trademarking the term 'Gracie Jiu-jitsu'. Clyde Gentry relates Rorion's viewpoint in No Holds Barred:

The term Gracie Jiu-jitsu was carved by me [in the USA] and it identifies my source of instruction […] When the Gracie name became very famous, a lot of relatives of mine started to capitalize on the work I had done. Unfortunately, they don't have the sense of professionalism and ethics that I wished they did and because I owned the Gracie Jiu-jitsu name, I would refuse to let those guys sell and prostitute the name.[57]

By 1994, Gracie jiu jitsu was making some major gains in the US market. That year, Carley Gracie took the decision to contest Rorion's trademark: after all, Carley was a Gracie too, who had been teaching jiu jitsu in the US for longer than his cousin. The resulting court battle went on for several years: the full proceedings can be found here.

The distinction between what Rorion had dubbed Gracie jiu-jitsu (GJJ) and what is now widely known as Brazilian jiu jitsu (BJJ) is in part a matter of politics (which Carley's legal tangles only served to intensify), along with the legal restrictions enforced by Rorion when he trademarked GJJ in 1989. Some might tell you that GJJ is concerned with self-defence, whereas BJJ is ‘merely’ a sport; others will say that there is no difference, it is just a matter of who is teaching. The Academy in Torrance has gone so far as to offer something called 'Gracie Combatives', which Rorion and his sons believe bring back the 'self-defence' aspect supposedly lacking in some other schools (for more on the course, see here and here, along with this and this ).

Carlson Gracie, in a typically forthright interview in 1997 with O Tatame, stated that "My Jiu-Jitsu is completely different from theirs, my technique has nothing to do with "Gracie Jiu-Jitsu". I AM CARLSON GRACIE and that's the way it is in the ring." [58] Kid Peligro, in a Fightworks Podcast interview, offers a different perspective:

To me, its always been just 'jiu-jitsu', because there is not a distinction in Brazil. I grew up just knowing it as 'jiu jitsu' [...] To me its Gracie jiu jitsu and Brazilian jiu jitsu: its all the same thing. We sweep, we choke and we get choked. I say it both ways, it doesn't matter.[59]

Rickson would seem to agree, responding to the question of what he calls his style by saying simply, "I'm Rickson Gracie, I practice jujutsu, and I'm from Brazil. You can think whatever you want. Heh, heh, heh. I'm not too much into names." [60]

Fabio Santos, who was already in the US when Rorion founded the Torrance school, remembers the early 1990s in an interview on the Fightworks Podcast:

One day, I grab a Black Belt Magazine and I find out that Royce and Rorion are living in LA, so I called them, and they're like "man, what are you doing in the mountains, you've gotta come out and train with us!" So I came to California, and that's where it all started back again. Rorion told me he had a big plan coming, if I wanted to help. I said "of course, I'm here to help, whatever you need", because they always help me, their jiu jitsu help my life, completely in every aspect, so I was there to help them, too.[61]

Thanks to Rorion's 'big plan', Gracie Jiu Jitsu (the term 'Brazilian Jiu Jitsu' had yet to fall into widespread usage) was about to become world famous, and Royce Gracie a household name. As Santos related in that same podcast, "I was teaching all the classes so Royce could go and train." All that preparation would soon pay off, as Royce readied himself to take part in the inaugural Ultimate Fighting Championship.

Royce Gracie and the UFC ^

Getting back to 1992, Art Davie and Rorion Gracie decided that taking the Gracie Challenge to a television audience would be an excellent – not to mention profitable – method of promoting Gracie jiu jitsu. They pitched the idea to John Milius, director of Conan the Barbarian, who proved equally excited by Gracie and Davie's concept, leading the three to develop a detailed plan by October 1992. Davie’s initial name for the competition was ‘War of the Worlds’, which in 1993 he presented to the Semaphore Entertainment Group (SEG), having exhausted all other alternatives. The proposal, together with the Gracie Jiu-Jitsu in Action tapes and the Playboy article, reached programmer Campbell McLaren and vice-president of marketing, David Isaacs. They convinced SEG head Robert Meyrowitz to go with the event, who trusted McLaren’s judgement. [62]

Rickson was the obvious choice to represent his family, as the acknowledged Gracie champion. However, it was decided that Rickson's much less muscular, unimposing brother, Royce, would fight instead, much to Rickson's displeasure. Clyde Gentry relates that Rickson argued "it's my fight. I've been waiting for this all my life", but was overruled. After an unsuccessful first trip to try and get a fight in Japan (he found a far more receptive audience there a few years later), he reconsidered, agreeing to train Royce for the competition. [63]

The Ultimate Fighting Championship was broadcast from Denver, Colorado on the 12th November 1993, without a great deal of coverage in the media beforehand. For the first time, vale tudo (Portuguese for 'anything goes') – in a modified form – would be seen outside of Brazil. The competitors were all experienced martial artists, but only Gerard Gordeau (a tough Dutchman who had been a bouncer and fought in Japan) and the shootfighter Ken Shamrock looked truly dangerous. Kevin Rosier had a legitimate record, but had been retired for some time, during which his once toned physique had softened considerably. Gordeau immediately justified his reputation in the opening bout of the televised show, knocking out the sumo wrestler Teila Tuli’s tooth in a matter of seconds.

Royce got an easy start against the boxer Art Jimmerson, who had little motivation to fight because he was being paid $20,000 simply to show up: wary of injury, he tapped almost immediately following Royce’s takedown. The Brazilian’s next opponent, Ken Shamrock, looked strong and skilful against Pat Smith, submitting him by a visibly painful ankle lock. Shamrock had experience in the Japanese Pancrase association, where he had learned to combine his history of wrestling with submissions, thanks to the tutelage of talented martial artists like Pancrase co-founder, Masakatsu Funaki. However, Shamrock was still comparably new to the sport, and had little experience with chokes, in particular when applied using the gi. As Shamrock sought to put Royce in position for his trademark ankle lock, Royce slipped his gi into place, choking out his much more powerful opponent.

Gordeau, given his impressive striking ability, had the potential to provide a difficult match for Royce, but fortunately for the jiu jitsu fighter, Gordeau was in poor shape by the time they met in the finals. Not only had he broken his hand, but two of Tuli’s teeth were embedded in his foot. Royce had little trouble taking Gordeau’s back and submitting him with a choke: Gordeau attempted to bite his ear in the process, but that only resulted in Royce holding the choke for an uncomfortably long time. It is difficult to say whether the contest might have gone differently had Gordeau been without injury, but on the other hand, Royce cannot be blamed for finishing his matches both quickly and without any damage to himself.

Gordeau, given his impressive striking ability, had the potential to provide a difficult match for Royce, but fortunately for the jiu jitsu fighter, Gordeau was in poor shape by the time they met in the finals. Not only had he broken his hand, but two of Tuli’s teeth were embedded in his foot. Royce had little trouble taking Gordeau’s back and submitting him with a choke: Gordeau attempted to bite his ear in the process, but that only resulted in Royce holding the choke for an uncomfortably long time. It is difficult to say whether the contest might have gone differently had Gordeau been without injury, but on the other hand, Royce cannot be blamed for finishing his matches both quickly and without any damage to himself.[for more on UFC I, see my summary]

Coming into the second tournament, Royce was no longer the smallest man in the competition who garnered little attention: he was the defending champion. His performance in UFC II was, therefore, perhaps even more impressive than his debut, proving his mettle in a tournament of sixteen rather than eight fighters. The much touted karateka, Minoki Ichihara, could do nothing against Royce’s grappling skill, despite bravely struggling to escape from mount. He would eventually tap to a gi choke, while Royce was simultaneously setting up an armbar. Jason DeLucia fared little better, despite having fought Royce once before at the Gracie Academy: he found himself trapped in an armbar in the midst of attempting to escape mount. Remco Pardoel, a much larger man with multiple national jujitsu titles, would also succumb, though he managed to resist for some time due to defending against Royce’s gi choke with his chin. Finally, Pat Smith, a kickboxer from the first event who had added a few submissions to his game, would tap soon after being taken to the mat.

Coming into the second tournament, Royce was no longer the smallest man in the competition who garnered little attention: he was the defending champion. His performance in UFC II was, therefore, perhaps even more impressive than his debut, proving his mettle in a tournament of sixteen rather than eight fighters. The much touted karateka, Minoki Ichihara, could do nothing against Royce’s grappling skill, despite bravely struggling to escape from mount. He would eventually tap to a gi choke, while Royce was simultaneously setting up an armbar. Jason DeLucia fared little better, despite having fought Royce once before at the Gracie Academy: he found himself trapped in an armbar in the midst of attempting to escape mount. Remco Pardoel, a much larger man with multiple national jujitsu titles, would also succumb, though he managed to resist for some time due to defending against Royce’s gi choke with his chin. Finally, Pat Smith, a kickboxer from the first event who had added a few submissions to his game, would tap soon after being taken to the mat.[for more on UFC II, see my summary]

The third event would be different. Rickson was unhappy that his brother Rorion was making a tidy profit from the UFC, while he himself made little. He and Royler set off on another trip to Japan, and this time round would find success first in Vale Tudo Japan '94 and '95 (the excellent documentary Choke, available on DVD, covers the build-up to the latter event and ensuing tournament), then some years later, in PRIDE. Already a legend in Brazil, Rickson would become a global figure: while he was given a dubious 400-0 record, there was nothing dubious about his skills in the ring. So impressive was his performance at Vale Tudo '94 that two of the three men he defeated would themselves take up Brazilian jiu jitsu. That included Yuki Nakai, who later earned his black belt and became a major figure in the Japanese development of the sport.

The fighters in UFC III reflected the shift in emphasis related by Gentry, when he refers to it as "a reality-fighting contest with a pro-wrestling spin." [64] The conflict between Royce Gracie and Ken Shamrock was hyped up, with the publicity posters for UFC 3 featuring the two men glaring at each other in a fighting pose. However, despite the promoters setting up the brackets so the two could meet in the final for a climactic end to the night, they never got the chance to fight.

In Royce's way was the immensely powerful and heavily tattooed Kimo Leopoldo (in a further nod to pro-wrestling, he was announced as simply 'Kimo'). Kimo was the most theatrical of all the fighters (though the charismatic Canadian karateka, Harold Howard, trumped him in the interview stakes), dragging a huge wooden crucifix on his back to the ring. Kimo had been introduced as a skilled taekwondo practitioner, but his third degree black belt was a fabrication.

Nevertheless, Gentry is a little too quick to label him "just a streetfighter" [65], as Kimo had a background in wrestling. The Seattle Times mentions a Kimo Leopoldo (I am assuming that is not a common name, but I could be wrong) in the Interlake High wrestling team, in two articles [66] from the 5th February 1985. On the 6th and 26th December 1985, The Seattle Times again mentions Kimo, and this time he is not merely a member of the team, but the defending champion at 190lbs with an unbeaten record of 9-0 [67] (a later article gives his full record for the 1985 season as 24-5 [68]). His age also fits, as Kimo was born on 5th January 1968, so would have been 17 at the time.

This would prove important, as Royce had yet to come up against a wrestler, particularly one as strong as Kimo. While Kimo had not wrestled for some years at this point, it was still possible to see that he had not forgotten his days as the 190lbs champion: e.g., at one point, he manages to reverse Royce's mount by bridging, which is not the action of someone completely untutored on the ground.

This would prove important, as Royce had yet to come up against a wrestler, particularly one as strong as Kimo. While Kimo had not wrestled for some years at this point, it was still possible to see that he had not forgotten his days as the 190lbs champion: e.g., at one point, he manages to reverse Royce's mount by bridging, which is not the action of someone completely untutored on the ground.Kimo's high school wrestling, combined with his considerable athleticism, caused Royce serious problems. He was also not wearing a gi, which was a major factor in Royce's defeat of Remco Pardoel, his only previous large opponent in the UFC with grappling experience. That meant that Kimo could slip out of Royce's holds, aided by the lubrication of sweat as the fight wore on.

Royce told Gentry that "This match was difficult for me. I tried to match power against power instead of all my other matches, where I used technique. I just wanted to see how strong he was." [69] Though Gracie eventually managed to catch Kimo in an armlock, he was absolutely exhausted. After coming out to fight his next opponent, Harold Howard, he still looked in bad shape. Royce remembers in The Gracie Way:

We stopped behind the curtains for them to announce my name and I got dizzy and said, 'Let me lie down here for a minute,' and I passed out. Then I woke up and said, 'Let's go.' I don't remember this, but they later told me that I asked for watermelon juice. […][70]

I was completely dehydrated and had low blood sugar. So when I got in the ring I got dizzy and everything turned black. Referee Big John McCarthy came to me and asked, 'Are you ready?' I said, 'Yes!' And I turned to my corner and said, 'Guys, I can't see anything.' McCarthy came back and asked again if I was ready and I gave him the same answer, yes. Again I turned to them and said, 'Guys, I am doing my job, you have to do yours. I can't see anything. What should I do?'

Seeing his brother in obvious severe difficulty, Rorion took the decision to throw in the towel. The champion was out, and even more bizarrely, Ken Shamrock would pull out too. Royce had been his whole reason for entering the tournament, seeking to avenge his loss in UFC. Shamrock's book, Inside the Lion's Den, written with Richard Hanner, gives the following reason: "He had prepared, he had hungered, to fight another professional, a man named Gracie. Now there was nothing to prove." [71] The two men over all the posters, all the marketing, all the merchandise, were out of the competition, despite having won their fights.

Seeing his brother in obvious severe difficulty, Rorion took the decision to throw in the towel. The champion was out, and even more bizarrely, Ken Shamrock would pull out too. Royce had been his whole reason for entering the tournament, seeking to avenge his loss in UFC. Shamrock's book, Inside the Lion's Den, written with Richard Hanner, gives the following reason: "He had prepared, he had hungered, to fight another professional, a man named Gracie. Now there was nothing to prove." [71] The two men over all the posters, all the marketing, all the merchandise, were out of the competition, despite having won their fights.Royce would redeem himself in UFC 4, in what was perhaps his best performance to date. His first opponent was, unusually, a fifty-one year old man named Ron Van Clief. His background was mainly in Goju-ryu karate, but he was most famous for his work as an actor in the Shaw Brothers films, where he had become known as 'the Black Dragon'. Van Clief was extremely fit for his age, but he lacked the tools to compete with Royce, who swiftly took him to the ground and choked him out. [72]

Keith Hackney proved much tougher opposition. The kempo stylist managed to defend against Royce's takedowns for much of the fight, landing some ground strikes, but was eventually caught in an armbar. That set up the climactic fight, against the very experienced wrestler, Dan Severn, who had both skill and strength at his disposal. Severn was perhaps Royce's greatest test during his time in the UFC, due to his many years of grappling, but Severn did not possess one very important quality: a willingness to punch.